Recreating a 14th century beverage using 21st century materials.

By Dýrfinna Tonnudottír

Bochet is a type of mead that is made from caramelized honey. This batch is based on a recipe found in the 14th Century book, Le Ménagier de Paris, a household guide compiled by a husband for his then 15-year-old bride. (Greco & Rose, 2009) Because I do not speak Medieval French, I used the 2009 English translation by Gina L. Greco and Christine M. Rose.

Mead has been consumed for centuries, and the earliest references to bochet date to 1292. (Verberg, 2020/3) The recipe from Le Ménagier calls for the honey to be boiled until it blisters and bursts, giving the beverage a toasted, nutty flavor. (Tarlach, 2021) What follows are the ingredients, materials, and methods that I used to create a bochet mead.

Materials

Ingredients

- 11 lbs Raw Honey

- 9 oz Raw Honey with Honeycomb

- 5 gal Water

- 1/2 oz Clove

- 1 oz Long Pepper

- 1 oz Grains of Paradise

- 1 oz Ginger

- 1 oz Cardamom

- 11 g Kveik yeast

- 1 Orange, quartered

Tools

- Stainless Steel pot

- Long handle stainless steel spoon

- 1 egg

- Linen spice pouch

- 5-gallon plastic brew bucket with lid

- One way valve

- Auto siphon

- 5-gallon jug

- Sanitizer

- 2 dozen 750ml glass wine bottles

- 2 dozen corks

- Corker

Brewing Process

Step One: Blister the Honey

Modern honey is harvested differently from what would have been available in 1392 – it’s extracted using sophisticated machinery rather than crushing the wax comb which would left pieces of the comb and other organic material in the honey. (Tarlach, 2021) In an attempt to get a close approximation, I purchased local raw honey as well as a piece of honeycomb which was melted into the honey during the boiling process.

The first step was to boil the honey for around 30 minutes, until the color was dark, and the honey began to foam slightly. (Tarlach, 2021) I did this on the stove because I do not have a cauldron or an open fire to cook over. I also chose to sanitize all my equipment using a no-rinse sanitizer to give my mead its best chance at developing without any outside bacterial strains introducing themselves via cross contamination.

I then added the water to the pot slowly because boiling honey has the potential to become a sugar volcano when disturbed. I boiled this mixture until it reduced, but I was still able to float an egg in it. An egg floats in a brew when there is enough sugar for the yeast to feed on.

I left the bochet to cool overnight before beginning the fermentation process. (Greco & Rose, 2009)

Step Two: Fermentation

Medieval brewers would have had access to different “brewer’s yeast” than what is modernly available for purchase. Much of what is available today has been created in clean labs, rather than medieval strains that were collected from wild strains. (Tarlach, 2021)

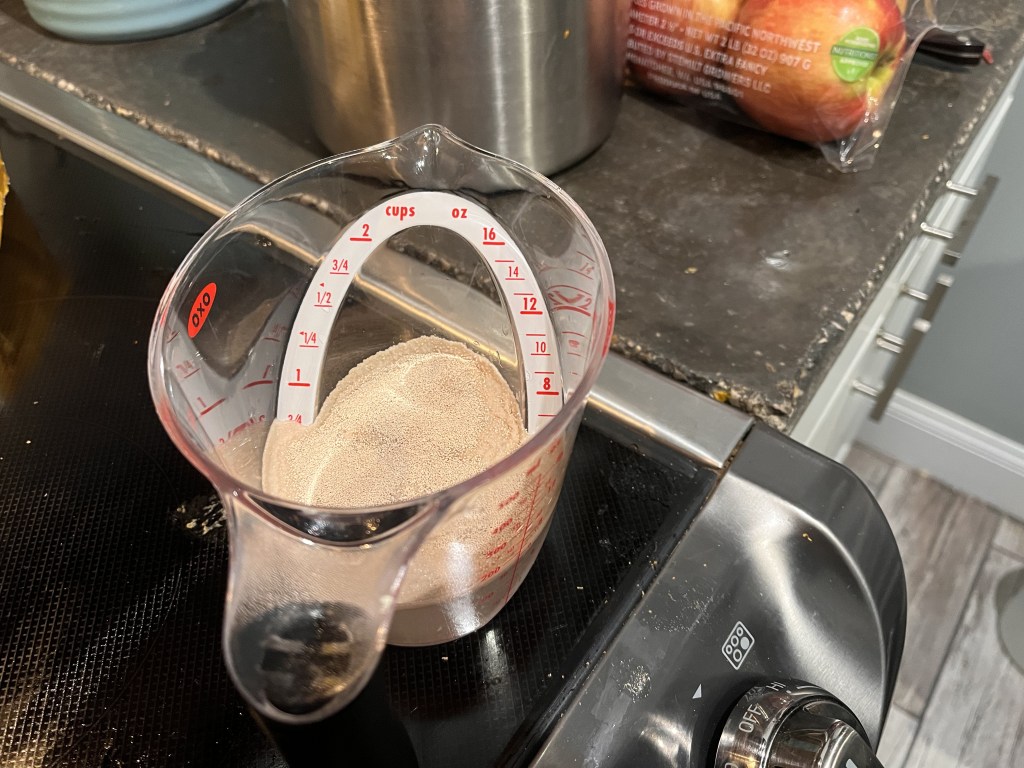

To begin the fermentation process, I added 11 g of commercial Kveik yeast to a cup of warm water and let the yeast dissolve until the water was cloudy with a little foamy layer on top. I chose Kveik yeast, because while it is not strictly a medieval strain it has been around for thousands of years and would have been somewhat like yeasts that brewers would have used in France in the 14th century. (Tarlach, 2021) This particular strain of yeast was recommended to me by the fine folks at Bacchus & Barleycorn.

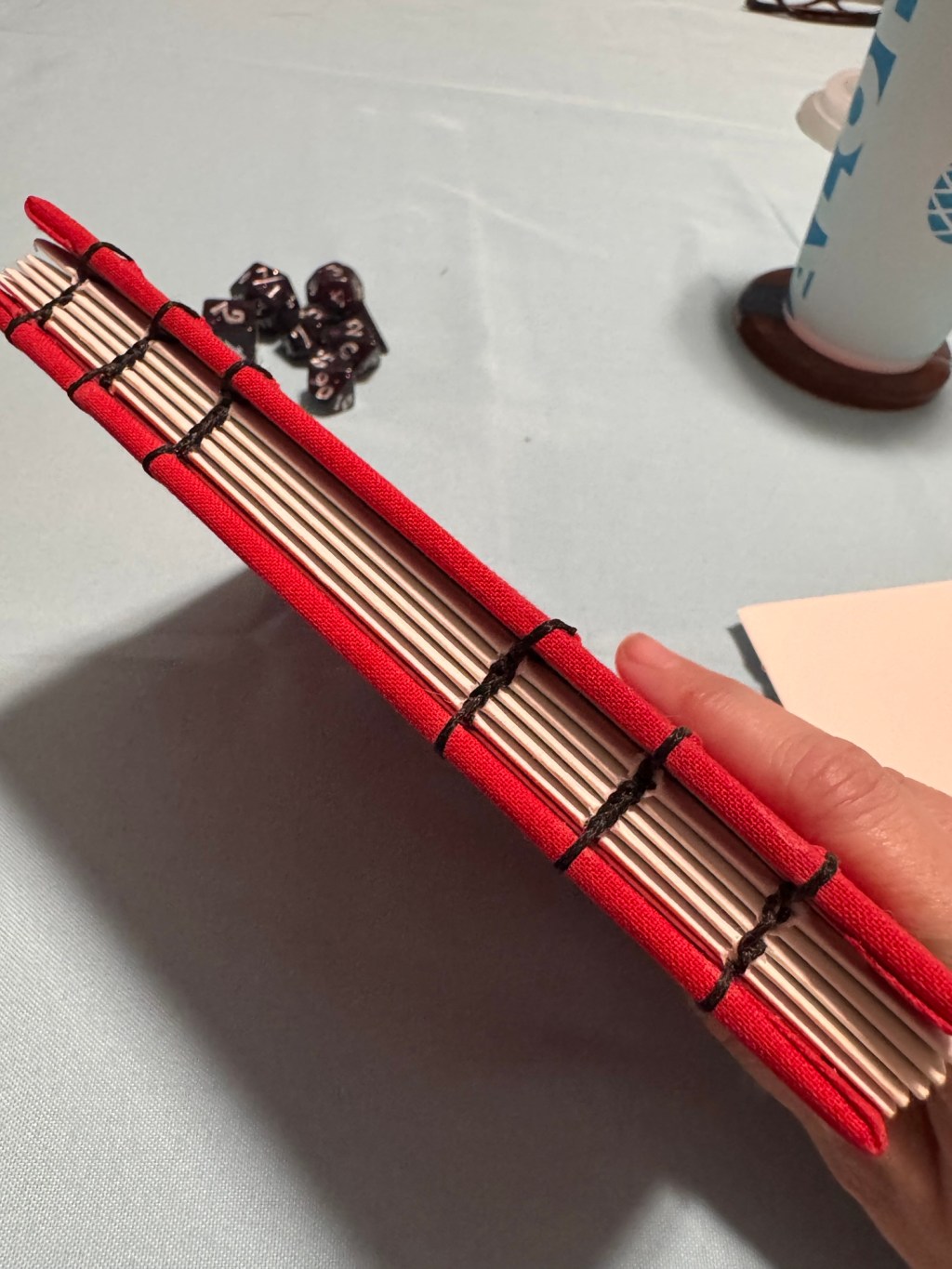

I added all the spices to a pouch made of linen – I didn’t intend to use the sachet more than once, so I used a piece of scrap linen and sewed the sides closed. The original recipe says that the spice bag can be used up to 4 more times for subsequent batches. (Greco & Rose, 2009)

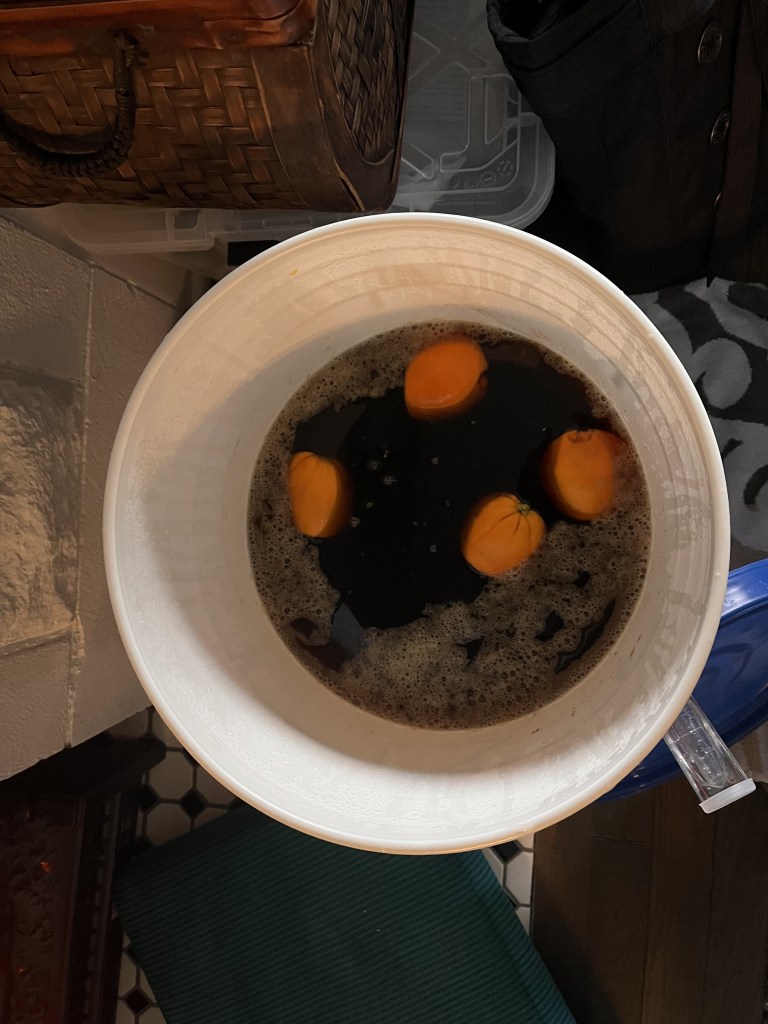

I threw the yeast mixture, spice bag, and the quartered orange (food for the yeast) into the plastic fermentation bucket and once it was sealed with a plastic lid I added the one-way valve to the top, which allowed fermentation gases to escape but no outside air to contaminate the brew.

I set the fermentation vessel in a warm spot in my home and left it to do its magic. After about three days, I removed the spice pouch and orange, and checked to see if the brew was still on schedule. Seeing no apparent signs of distress, I left the brew to continue fermenting for several more weeks.

This part was definitely the most stressful for me, because all of the action was being done by microbes and there wasn’t anything for me to do but sit and wait for them to slow down.

Step Three: Racking

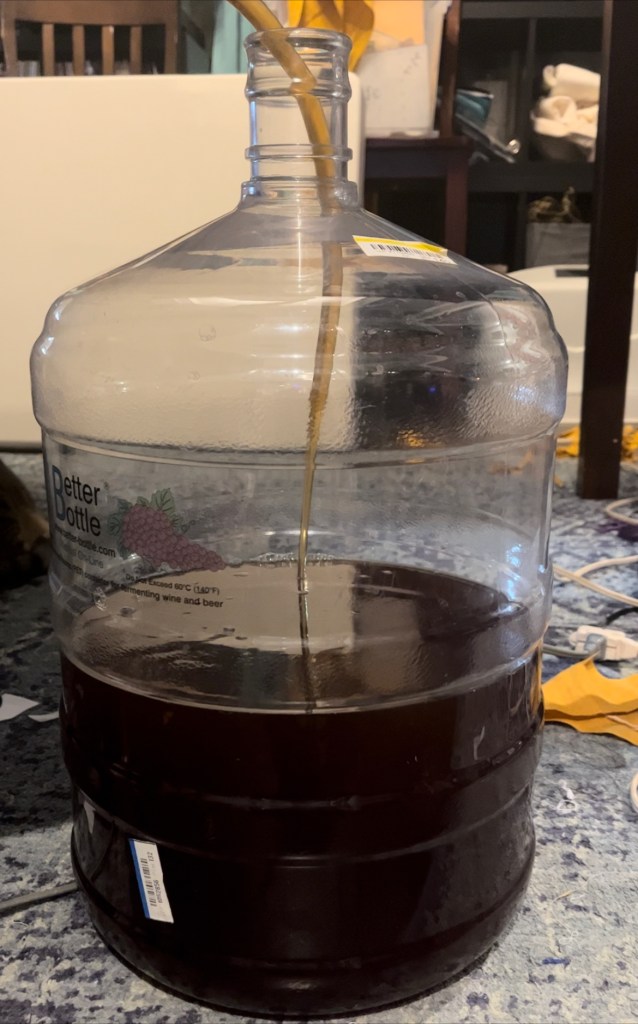

After about a month, I used the auto siphon to move the bochet from the fermentation bucket to a sanitized carboy – a plastic five-gallon jug that approximates the keg that it would have been stored in to finish.

I wrapped the carboy in blankets to provide a dark environment for the brew to continue processing, and moved the one-way valve to a plastic stopper in the vessel that would continue to allow gases to escape.

I left the brew again for another month. I will neither confirm nor deny poking at the carboy to see if it was still alive.

Possibly more than once.

Step Four: Bottling

While some meads can be aged for six months or more, I had a short timeline to stick to if I wanted to be able to present this mead at the Queen’s Prize Tournament.

Since fermentation was done, and most of the remaining gas by-product had dissipated after about a month in the carboy, I decided that the bochet was clear enough to bottle and share.

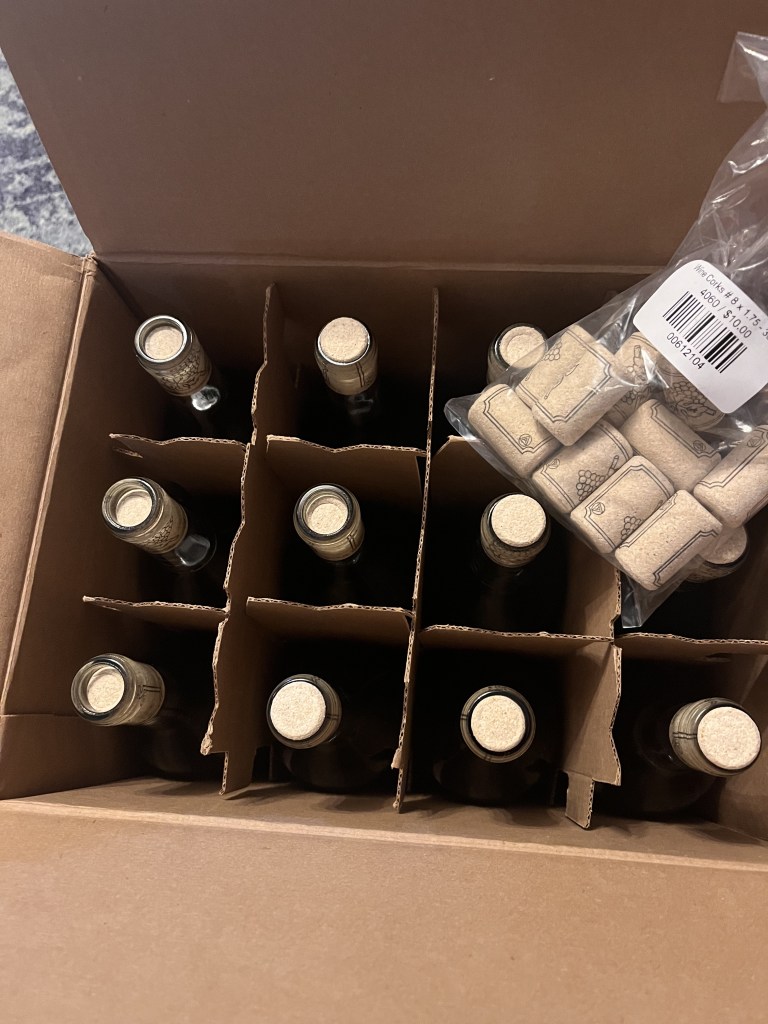

I used the auto siphon again to decant the mead into 20 glass bottles and plugged the openings with synthetic corks. Real cork can be cost prohibitive and difficult to find, so I went with my readily available substitute.

Conclusions

The extant recipe source was intended to be a household guide for a young French wife, but in many places in Europe, the most popular drink from the 1300s to the late 1700s was actually ale. Female brewers, alewives, often brewed in their homes and frequently sold the excess to local customers. (Kuligowski, 2023) Given that information, its plausible that this mead would have been brewed at home, but it also could have been purchased from another gentle.

This mead was a lot different than commercial meads that I’ve tasted – the charred flavor of the honey kept it from being overly sweet though I feel like the bochet will continue to develop well for several more months. I’ve set aside a couple of bottles that I will continue to age to see what happens after another 6 to 12 months in a cellar.

Were I to make this again in the future, I would love to invest in a large enough cast iron cauldron so that I could boil the honey over an open fire – a kind SCA friend has volunteered their land for such future experiments.

Original Recipe

To make 6 septiers of bochet, take 6 quarts of fine, mild honey and put it in a cauldron on the fire to boil. Keep stirring until it stops swelling and it has bubbles like small blisters that burst, giving off a little blackish steam. Then add 7 septiers of water and boil until it all reduces to six septiers, stirring constantly. Put it in a tub to cool to lukewarm, and strain through a cloth. Decant into a keg and add one pint of brewer’s yeast, for that is what makes it piquant – although if you use bread leaven, the flavor is just as good, but the color will be paler. Cover well and warmly so that it ferments. And for an even better version, add an ounce of ginger, long pepper, grains of paradise, and cloves in equal amounts, except for the cloves of which there should be less; put them in a linen bag and toss into the keg. Two or three days later, when the bochet smells spicy and is tangy enough, remove the spice sachet, wring it out, and put it in another barrel you have underway. Thus you can reuse these spices up to 3 or 4 times. (Greco & Rose, 2009)

Bibliography

Greco, G. L., & Rose, C. M. (2009). The Good Wife’s Guide (Le Ménagier de Paris): A Medieval Household Book. Cornell University Press.

Kuligowski, E. (2023, January 30). Alewives In Oxford: A History Of Female Brewing. Retrieved from Museum of Oxford: https://museumofoxford.org/alewives-in-oxford-a-history-of-female-brewing

Tarlach, G. (2021, August 12). The Quest to Recreate a Lost and ‘Terrifying’ Medieval Mead. Retrieved from Atlas Obscura: https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-to-make-medieval-mead-bochet

Verberg, S. (2020/3). An Analysis of Contemporary Sources to Uncover the Medieval Identity of the Drink Bochet. EXARC.

Leave a comment